Public Lecture Presented at Barnard Forum on Migration, Barnard College, Columbia University, New York, United States, November 7, 2007

The Transnational Express:

Moving Images, Cultural

Resonance and Popular Culture in Muslim

Northern Nigeria

Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

Department of Mass Communications

Bayero University, Kano – Nigeria

(Vice-Chancellor of the National Open University of Nigeria)

auadamu@yahoo.com

Abstract

This paper explores the migration of entertainment media from transnational sources to Muslim Northern Nigeria, and explains how the new media form attempts to negotiate the tension between cultural resonance of the media messaging and an Islamicate society operating newly re-introduced Shari’ah Muslim law. The presentation analyses this migration of media cultures in two dimensions. The first was through what I refer to as “cultural downloading”— the process by which Hindi films were directly appropriated into Hausa video films. The second was how the American "War on Terror" became a subject of comedic reinterpretation of the “clash of civilizations” in an Islamic visual entertainment through reenactment of the American response to the 9/11 incident – which provides an insight into the role of spectators in a larger transnational drama.

Introduction

The Hausa video film industry came into

commercial existence in 1990 with the release

of Turmin Danya by Tumbin Giwa Drama

Group in Kano. The group was made up

of TV drama artistes who wanted to extend their range of filmmaking to include the video format which was being

exploited and popularized by southern Nigerian filmmakers. From about 1990 to

1999 the general format of Hausa video films

tended to reflect the traditional tale of either romance and co-wife rivalry,

with occasional forays into gangland

warfare as typified

by the social and political

upheavals of urban Kano in the 1980s

and 1990s.

When the debates about the cultural implications of the more commercial Hausa video film started after the appearance of

video films exploring adult domestic scenes in

1999, the main focus was on the cultural implications of such video

films. What brought about the debate

was the clearly different cinematic techniques adopted

in the video films and those used in

the traditional TV drama series.

And in fact in recognition of this difference of styles of storytelling, some

Hausa video film stars, especially

Shehu Hassan Kano (whose opinions were given in Film, March 2006 pp 33-34) were keen to point out that they are making “films” not “drama”.

Such differences were indeed imposed on

the producers. The traditional TV dramas popularized by NTA networks

in northern Nigeria

had distinct patterns

and styles and were

sponsored by established companies such as Lever Brothers, PZ, GBO etc. These companies market essentially

domestic products – soap and detergents, cooking items, mattress, toothpastes,

etc – and the drama series they support must reinforce family values and systems. What comes out was a series of dramas based on wholesome family entertainment values.

Further, the early TV drama producers lacked

the technical equipment to follow characters to every location, and therefore had to take advantage of natural

lightening. This necessitated scenes being shot outdoors as much as possible.

A further technical imposition on the family values of early TV drama producers was the

structure of the Hausa household. With a zaure,

a corridor and an open atrium, “tsakar gida”, the division between

private and public

spaces are clearly

delineated in typical Muslim Hausa dwellings. The TV

drama series producers were careful not to reveal

bedroom – conjugal family spaces – in their films, and in all circumstances avoided

scenes where a man and a woman would have to be seen in bed. Further,

the women who appear in the TV drama series were matronly

– elderly and de- sexualized, such that they can only appear

as either mothers, aunties or at the very least, elder sisters. Dialogue

and interaction among the stock characters was predicated

upon the strict division between the private and public spaces – female guests

are received in the “tsakar

gida”, and rarely

in the inner bedrooms; male guests are received in the zaure. In fact to make it easier to receive male visitors, traditional houses often have a frontage

dakali, a cement “bench”

on which the head of the house

receives more informal

visitors.

The critical theory propounded by Jürgen Habermas

in his The Structural Transformation

of the Public Sphere (1962) provides a convenient framework for further understanding the division between

the private and public spaces, and most especially

in Muslim communities where the distance imposed by space between genders in public is strongly enforced.

The particular appeal of this critical theory is in providing an analytical base that offers an opportunity to

determine the impact of extraneous

variables in the delineation of space in traditional societies. At the same time, it provides an insight into the

application of the critical theory in a traditional society negotiating a redefinition of its public spaces within

the context of media globalization.

I would wish to make it clear, however,

that in this study, I focus attention on the

visual media re-enactment of the female

private space in an Islamicate environment,1 and the critical reaction

of such process

from the properly

constituted representatives of the public

sphere. As Nilüfer

Göle (2002:174) notes,

The public visibility of Islam and the specific

gender, corporeal, and spatial practices

underpinning it trigger new ways of imagining a collective self and

common space that are distinct from the Western

liberal self and progressive politics.

Such public visibility includes

breaking the conjugal space barrier by video cameras to film an essentially conjugal

family space and bring it to the attention of the public.

In this therefore

I do not focus attention

on participation of Hausa Muslim

women in negotiating what I

refer to as “space chasm” that separate their private and public spheres

in their attempts

to be part of the Hausa Muslim

economic system.

The “public sphere” to which Habermas refers encompasses the various venues

where citizens communicate

freely with each other through democratic forums (including newspapers and magazines, assemblies,

salons, coffee houses, etc.), which emerged with the formation

of a free society

out of the nation-state in 18th century

Europe. The public

sphere in its original form functioned ideally

as a mediator between the private

1 I adopt Asma Afsaruddin’s (1999)

usage of Marshall

Hodgson’s term Islamicate (1974:1:58-59), for the subsequent

“modern” period (roughly from the 19th century on) to describe societies which maintain and/or have consciously adopted

at least the public symbols of adherence to traditional Islamic beliefs and practices.

sphere of the people (including family

and work) and the national authority, which engaged in arbitrary politics, although in our application dealing

specifically with the sub-national issue of Muslim

laws of female

identity in northern

Nigeria.

The public sphere exists between the

private sphere and the public authority. The

participants are privatized individuals, who are independent from the public

authority, enjoying cultural

products and discussing about them. As the institutionalized places for discussion such as salon,

coffee house and theater increased, the places for family became

more privatized and the consciousness about privacy strengthened more.

“As

soon as privatized individuals in their capacity as human beings ceased to

communicate merely about their

subjectivity but rather in their capacity as property-owners desired to influence public power in their common

interest, the humanity of the literary public sphere served to increase the effectiveness of the public sphere in the

political realm.” (Habermas 1989:56)

Public opinion produced in public

sphere started to have an influence on legislating law, which overarched the monarchic power and became

the universalized. Further,

Included

in the private realm was the authentic ‘public sphere’, for it was a public

sector constituted by private people.

Within the realm that was the preserve of private people we therefore distinguish again between

private and public spheres. The private sphere comprised of civil society in the narrower sense, that is to say, the

realm of commodity exchange and of social labour;

imbedded in it was the family with its interior

domain (Intimisphäre). (Habermas 1989:30)

Habermas himself even gives a schematic structure of the division between the private

realm and the sphere of public authority

(1989:30).

Private Realm Sphere of Public Authority

|

Civil society

(realm of commodity exchange and social

labor) |

Public realm

in the political sphere |

State (realm of the ‘police’) |

|

|

Public sphere

in the world of letters (clubs, press) |

|

|

Conjugal family’s internal space (bourgeois intellectuals) |

(market of culture products) ‘Town’ |

Court (courtly-noble society) |

Thus

as Talal Asad (2003) pointed

out, the terms “public” and “private” form a basic

pair of categories in modern liberal society. It is central to the law,

and crucial to the ways in which liberties

are protected. These modern categories are integral

to Western capitalist society, and they have a

history that is coterminous with it. A central

meaning of “private”

has to do with private

property, while “public”

space is essentially one that depends

on the presence of depersonalized state authority.

While

Habermas was primarily

interested in “rational-critical” communication as the ideal

standard of modernity, he identified its practical emergence

with the intermediate space of coffee-houses and salons, where private

citizens could assemble

as a public, between the private space and personalized authority of kin and the public realm marked by the theatre of royal and religious

ritual. It was set apart from those

by communication that had to be

convincing without the external support of the

authority of the speaker.

Hausa Filmmakers and the Religious

Establishment

While

there were continuous grumblings and complaints about cultural misrepresentation in Hausa home video

films from readers of the popular magazines

that were established in the period (1999-2001), none of the films up 1999 paid close attention to religious issues.

A typical complaint

was:

“I

am calling on producers to focus attention on films that are appropriate to

Shari’a. This is because of the

numerous complaints from people (civil society), especially the song and dances.

People are saying

these are not appropriate to our religion

and culture. Why should we not

show our pure culture, without borrowing from others? Or is our culture

inadequate? I am calling on them

therefore, for the sake of Allah, to try to reduce the songs where a boy and a girl sing to each other”.

(Alhaji Rabi’u Na Malam, Letter Page, Fim December 2000 p. 8).

The

first Hausa films that started

to drew the ire of the culturalist establishment were Soyayya Kunar

Zuci (“Love Burns the Heart”,

1995, Jos) and Alhaki Kwikwiyo (“Sin is a puppy, it follow its owner”, 1998, Kano). Both were

directed by late Mr. USA Galadima, a

veteran director based in Jos. Both were shot with Betacam and not the VHS format that was to become standard for

Hausa home video films. However, although

Alhaki Kwikwiyo was subsequently

released on VHS, Soyayya Kunar Zuci was never released on video. Each of

these films were accused of being too adult for the conservative Hausa audience.

Soyayya Kunar Zuci is a story of lovers

who eloped to escape their parents opposition to their friendship. While on the run, the girl becomes

pregnant. Both the mother and the

baby die at the baby’s birth. It was the process of the girl getting pregnant, obviously

involving some form of nudity that created

the most concern

to the cinema audience when

it was screened in 1995. Defending her role in the film, the leading actress

Aisha Bashir stated

in an interview:

“This

is just drama (not real life), and if you know what you are doing (as a

character) you should know that (the

scenes depicted in the film) are not part of our culture. Our purpose in the film is to warn our people about these

kinds of behaviors (elopement and unwanted pregnancy)

which are typical of Turawa (white

people). Our people should respect their culture…Soyayya Kunar Zuci is my best film and I

am proud of it.” Interview with Aisha Bashir, Fim, March 1999

p. 7).

Alhaki

Kwikwiyo was released in December

1998. The video film was based on a woman’s

empowerment novel of the same name by Balaraba Ramat Yakubu. It chronicles the story of a woman whose

husband was not happy with the fact that she

gave birth to five girls. He decided to divorce her and subsequently

married two younger wives,

one after the other. The central themes of the film are two – kishi,

and the empowerment of the

divorced “senior” wife. It was in the way the principal character interacted with his wives, and the fact that their kishi was

explored principally through

their competition for his sexual

attentions that earned

the film the label of batsa (obscene).2 According

to a viewer:

2 Strictly, “batsa”

means foul – whether in language or behavior. It is a generic term for any

behavior that has sexual overtones,

and can include both soft and hard core of pornography; although in the context

of Alhaki Kwikwiyo, it refers to the numerous

scenes in which the principal

character either

“This film is good and an improvement. But there are three places

that need to be censored

for the general release of

the tape. First was the scene where Alhaji and his wife were shown on bed together. Second where one of the

wives was seen giving her houseboy a massage in an adulterous situation. Third where a flash of the pant of one of

the wives was shown in a domestic

violence scene. If they remove these scenes it can be suitable for general

audience. But if they don’t, then it

is not proper to take it to our homes for children to see.” If they restrict it only to cinema, there is no

problem.” A viewer, at Kofar Mata Stadium after the premier showing of Alhaki Kwikwiyo, Fim, March 1999 p. 9).

Before Alhaki Kwikwiyo

was released on tape, already

the news of the film’s

content had spread

throughout northern Nigeria. Cassette dealers in Kaduna were the first to react

against the film when one of them stated:

“We

will not sell this tape (Alhaki Kwikwiyo)

when they release it because it goes against our culture and religion. It is clear there is some form of nudity

in the film, and in our position as Muslims,

it is prohibited for us to make films with nudity. We have told the producers

if they want us to distribute the

film, they have to remove a lot of things (nudity).” Mustapha Mai Kaset,

Kaduna, in an interview with Fim,

March 1999 p. 12.

However, in almost rapid succession

three video films were released that all proved catalytic to the establishment of hitherto unheard of censorship

mechanisms. The specific video films to attract the wrath of the Muslim scholars were Saliha?, (“pious?”), Jahilci Ya Fi Hauka (“Ignorance is harder to cure than lunacy”) and Malam Kartata

(“Teacher, watch your entry point”).

The first two were both released in 1999, while the third, produced, but

never released in 2000, was a more serious adult-themed drama.

I will now look at the evolution of each of these films and how they contributed to the idea of censorship in northern Nigerian

home video film industry.

Saliha?

Both the religious and government

establishments had, up till 2001, largely ignored the home video film phenomena. Indeed except for children, youth

and housewives, the entire Hausa home

video remained largely ignored by the large sections of the civil society. The Muslim scholar

community took notice of the industry only when Saliha? was released

in 1999 in Kaduna. The video was widely condemned as ridiculing Islam and the Muslim female, especially her hijab—the head covering. According

to the video’s blurb:

Saliha? is a Hausa home video portraying the importance Hausa culture attaches

to the preservation of the virginity of female child

before marriage.

Saliha?

chronicles the life of a deeply

conservative and apparently religious Hausa Muslim girl constantly clothed

in hijab (the Muslim

female head covering)

to further accentuate her modesty and piety. After

she got married she passed on to her husband

a sexual transmitted disease (not AIDS)—clearly indicating that despite

her religiosity, she was sexually

promiscuous.

touches his wives or appear semi-naked with them on beds, or where one of the wives was seen massaging her houseboy.

The furor that the video created was to a large extent

caused by the fact that the video

was, like almost all Hausa video films, split into two parts. Part 1 was

first released and told the story up

to Saliha’s nuptial night, when her husband was bitterly disappointed to discover she was not a virgin (the video did not

explore whether he was also as “pure” as he expected her to be – reflecting a moral burden

on the female character,

at the exclusion of the male, in most Hausa video films), and to cap it, a few days later he discovered he had contracted a sexually transmitted disease. Tests at the laboratory showed he contracted it from her.

The release of this section of the

entire drama only in Part I of the video, which did not of course show how it was resolved, gave the impression that

apparently pious girls (thus the

question mark on her name, Saliha,

which meant pious and is also a common Muslim Hausa name) are not all they

seemed to be. Thus the audience did not

wait to watch part two of the drama before pouncing on the producer and the director.

In Part 2 of the video, which was

hurriedly released to complete the story, the

producers provided flashback scenes about how Saliha lived her life

before the marriage. It would appear

that despite the piety she was a “loose” girl, with a boyfriend from whom she contracted the disease.

Yet if anything, it only confirmed to the critical

audience the hijab, a symbol of sacredness, has been profaned.

The video drew massive controversy and

condemnation, including a “fatwa” on the producer

by a religious group in Zaria.3 In an advertorial, the producer

explained his motive by insisting

that he wanted to draw attention to the need for istabra’i, a waiting

period which a Muslim woman who had lived a free lifestyle must undergo before getting married, and which in the

character in the story did not observe.4 In a direct quotation in an interview, the producer was recorded as saying:

“I did not produce the video

with the intention of causing any controversy, and Allah is my witness.

I am (therefore) seeking His forgiveness for any mistakes

that are in the video.”

(Fim, November 1999 p. 22).

A year later, in retrospective bravado,

the producer denied this statement in another

interview with Fim in which he stated,

“I

can’t recall seeking for any forgiveness over this video (Saliha?). What happened was that

those who issued

death sentence on us actually

demanded an explanation about our motives

in making the video. I

explained myself in radio interviews. What I did was that after the furor generated

by the video, I consulted

learned Muslim scholars

about accusations against

me and the my motives for doing the video. All the scholars I

consulted assured me that if I were killed

on these reasons alone, it would be murder, which is contrary to Islamic ruling

on such issues. So I am saying if

they had killed me, I would have died a martyr.” (El-Saeed Yakubu Lere, Producer, Saliha? in

interview with Fim, December

2000 p. 59).

The death sentence

was eventually removed.

If anything, the incidence awakened

the Muslim community

to the fact the Hausa home video can be used a medium of

3 The producer received a threatening letter on 27 July, 1999

instructing him to withdraw the video from

the market, issue a public apology for doing the video in the first place, or

be ready to die. Fim, November

1999 p. 21.

4 Advertorial, “Fim ‘din Saliha? Ya

Ciri Tuta”, Fim, July 1999 p.29.

messaging – and the message may not always be what they want. Viewer reaction

was equally furious,

as typified by this angry correspondent to a magazine:

“Before

the appearance of Saliha? young girls

and women who loved wearing hijab became tarred with the same paintbrush as those who don’t like hijab. Night or day, whenever a girl or woman

with a hijab is sighted, you often hear sniggers of “Saliha?”, indicating a hypocrite. Almost

at once, many women stopped

wearing the hijab,

for fear of being equated

with Saliha of the film Saliha? Similarly, those who are not Muslims, and who hate Islam

will now seize the opportunity to label all Muslim women

hypocrites, especially as the film is produced

by an insider (i.e. a Muslim)”. (Hajiya

Ali, Tauraruwa magazine Letters

page, August 1999, p. 2).

Like in most controversies, there was

some support for Saliha?, as

indicated by the following letter’s

page correspondent:

“The critics

claimed that Saliha? was to meant to disgrace

the hijab. In my view this is not so. People

seem to forget this is drama. Also

the title says Saliha?, the ? is a query…the critics are just being selfish, otherwise the film illuminates us about ugly dogs biting

hardest, because all those holier-than-thou types may

have a secret or two to hide. And yet they are threatening to kill the producer! Why? For just

producing a film? I recently heard him explaining himself in Jakar

Magori (a Radio Nigeria, Kaduna program). I really pity him.” (Abdulganiyu

A. Ango, Fim magazine letter’s page,

December 1999 p. 7).

Eventually the furor died down, but it

served as a bitter lesson to other producers,

since no other film appeared

that seem to cast integrity on the Muslim female.

It also shows clearly the

clash that is likely to occur when media technologies are used in a powerful way to portray

social issues. The refusal of the critics

to distinguish between

drama and real life show the balance

of credibility needed in using media technologies in visual messaging in traditional societies.

Jahilci Ya Fi Hauka (JYFH)

While controversy over Saliha? was still raging, another video

with religious theme was released

also in 1999 in Kano. This was Jahilci Ya

Fi Hauka, a devastating comedic

take on Hausa Muslim scholar mendicants, and at the core a cautionary tale about trusting Muslim scholars without

accrediting their knowledge or authority. It

portrays the machinations of some Muslim

scholars in their relationship to society as well as women.

It focuses on the chronicles of a

wandering marabout, “Al-Sheikh Ibro” (played by Rabilu Musa Danlasan, a comedian), with a shallow knowledge of

Islam, and yet portraying himself as

a scholar of immense knowledge, and preying on gullible citizens, especially women

who want him to give them charms and chants

to ward off a husbands

intending or resident

co-wife (kishiya). This mendicant

was counterbalanced by a more

knowledgeable Malam who corrects the mistakes of the charlatan “Sheikh”.

While the video film narrates his escapades in a typical community, the

trigger that caused furor was a song

and dance sequence in the film, the Rawar

Salawaitu (the Salawaitu

dance), a particularly energetic dance which was led by the Sheikh himself.

The dance was performed by five women

who came to the mallam

seeking chants and charms.

The mallam insists on the dance as part of his consultation fees. The dance involves

the entire body, especially the derriere, shaken

vigorously and suggestively. Even the camera artwork was rigged to focus exclusively on the breasts and derriere

of the women dancers. In one of the

scenes, he became so sexually aroused that he

was seen battling with a raging penile erection (“gora”5) after a sexually arousing dance from one his women visitors. Even the characters’

dressing, mode of speech and

instruments of religious worship such as the ridiculously over-sized rosary (“charbi”) beads which is referred to as firgita jahili

(frighten an illiterate) is a caricature of a Muslim mallam.

JYFH generated a lot of debates in

Kano, principally among those who felt that the Hausa Muslim malam, a revered member of the civil society, has

been desecrated.6 Typical reactions included:

“In his video film, Jahilci

Ya Fi Hauka, he made women dance, and the dance was not appropriate. Malam Ibro, you should be

aware that children and youth watch

these films and they can imitate what

they see. I hope you will correct in future. And you should stop using swear

words in your films, it is not appropriate, because you are supposed to be

teachers, not destroyers of good manners.” (Ibrahim Muazzam Yusuf,

Fim, July 2000 p. 5).

And

“Jahilci Ya Fi Hauka is disgraceful. Has

the film elevated or downgraded Islam? What does “Salawaitu” mean? Where did they get the word? If we call the women who did the (Salawaitu) dance prostitutes, are we

wrong? Please take care for the future!” (Abubakar Usman, Fim,

October 2000, p. 5)

The

religious establishment did not specifically react against the film, simply

because they were not even

aware of it—since they rarely watch such films. However in an interview, the producer of the film (an actor who appears

in the film as being the more rational

mallam than Ibro’s charlatan Sheikh Ibro, and who himself is a well-versed Islamic

scholar) depended it:

“Despite

the complaints of viewers about JYFH, it is my best film because of two

reasons. First it has brought me out

as an actor. Secondly I want to express my concern about the way some Malams behave, and we used the film

to illustrate the dangers of ignorant Malams.”

Interview with Malam Dare, Garkuwa, December

2000 p. 38.

His defense for the film remained

consistent, as he further clarified in another

interview three years after the film was released:

“Sure

I have heard (the furor against the film), and they are still at it. It is

however a mistake for people to

condemn the film. I have tried several times to draw the attention of people towards this ignorance about the role of

film in social messaging. We have portrayed the wealthy, the poor, the ignorant,

the rulers. We have shown the good and bad attributes of each of these class of people. So what is

surprising when we portray Muslim scholars? There are bad ones as well as good ones among them. Thus when you show a

disease, you should also show its

cure. And everything that Ibro did in the film Jahilci Ya Fi Hauka, there are some Muslim scholars in our communities with these kinds of behaviors

(Interview with Auwalu Idris (aka Malam Dare),

Fim, August 2002, p. 21).

The fact that the Hausa Muslim scholar

community had never commented on the Hausa

film industry was essentially because they did not see it as a culturally threatening influence. Islamic culture

has been strongly

entrenched in the mindset of

5 A knobby stick or club – a perfect

metaphor for a penile erection.

6 The forum for expressing these views were public gatherings, radio phone-in shows on Radio Kano, and Hausa popular

culture magazines such as Garkuwa,

Fim, Annashuwa, Nishadi.

the

Hausa such that if years

of media parenting

with Hindi film bombardment did not produce a community of idol-worshipers

(despite cramming thousands of Hindi film soundtracks

which paid tribute, one way or other, to Hindi idols), then certainly the Hausa

home video would not. The industry came to their notice only when it challenged their moral space. More was to come with the public screening of Malam Karkata in 2000.

Malam Karkata

With the public outcry about JYFH still ringing, the third catalytic video film appeared.

This was Malam Karkata

(2000, Kano) which was first (and only) shown at Wapa Cinema,

Kano in April 2000—few months before the Shari’a was re- launched—and created the first conduit to censorship in Kano by attracting widespread condemnation from the patrons because of its seemingly sexual innuendos and suggestions. This was more so in a

polity already sensitized to Shari’a and religiosity.

Malam Karkata explored an adult situation in which gullible Hausa housewives in their search for chants and charms to

either dominate their husband’s co-wives or their

husbands (or both), were manipulated by marabouts. The malam in the film always insists on sexual gratification

from his female clients. In the course of his

nefarious activities, he contracted HIV/AIDS.

The title of the film is itself

a direct sexual

reference to a sexual position, thus geared towards revealing the activities of such

marabouts. The video film is an attempt to highlight the issue of sexual harassment in Hausa societies and how women are taken

advantage of by unscrupulous marabouts. It also contained

a message about HIV/AIDS.

Reaction to the film in Kano was immensely negative, and the cinema did not screen

it again. As a result of this reaction, the film was never released for

general viewing. The film was seen

as another firing salvo at the credibility of the Muslim scholar community. However, in an interview with Tauraruwa (September 2000 p. 12), the Executive Producer explained

that the film was targeted

at adult audience, and was in fact

based on real true life story, rather than fiction—proving that truth is

stranger than fiction.

Similarly, in another interview, the principal character of the film, who played the role of Malam Karkata, Alhaji Kasimu Yero, a

veteran TV drama star, explained his involvement thus:

“How

can I regret my role in this film (that has been banned by marketers)? We had

good intentions in doing the film.

The film is about a godless Malam, Karkata, who uses his position to sexually abuse vulnerable women who come to him for

spiritual consultations. We balanced

his character in the same film with the life of a God-fearing Malam who always admonishes and advices women coming to him

seeking chants and charms to harm their husbands or their husbands’ other wives, informing his clients that he did not learn

such things in his studies. What is wrong with this

message? At the end of the film Malam Karkata

contracted HIV/AIDS from an infected

girl, and his life entered

into a real doldrums. Here,

we want to warn Muslim

teachers that beside this terrible sin of unlawful sex which will be severely punished by Allah, they are also

endangering their health with their lust”. Kasimu Yero defends his role in Malam Karkata.” Interview, Fim, October

2000, p. 46).

In any event, Malam Karkata was never released commercially. Interestingly, the same storyline was used by a producer in

Sokoto and a film, Nasaba, was made

in 2004. In Nasaba, instead of a Malam sexually abusing his client, his role

was taken over by a witchdoctor (boka)—a move to deconstruct the role of boka in Hausa societies.7

Two other Hausa video films that

further contributed to the censorship debacle in Kano were Sauran Kiris (2000) and Kauna (2000). Like the Hindi cinema most copy, Hausa home video

producers were careful

to avoid particularly inter-gender physical contact in romantic scenes. Sauran

Kiris, with a suggestive poster of a couple,

looking deeply at each other,

and seemingly about to

kiss (thus the contextual meaning

of the title, kiris or

almost) bucked this trend and generated heated condemnation from viewers — and improved sales, since those

who were not even aware of the video rushed out to buy it to see just what the fuss was all about!

Similarly, Kauna featured some of the most powerful

acting by Abida

Mohammed in her role as a deaf person, and thus

focuses attention on the problems faced by those with disabilities in Hausa societies. However, the video drew a lot of criticism due to the extremely “sexually suggestive” dance routine of the same Abida Mohammed

in it

— thus negating the seriousness of the subject matter of disabled

persons.8

The public reactions to these films

reveal the conflicts that exist between techniques of filmmaking that reproduce the family conjugal sphere and

traditional Islamic values. The reinforcement of privacy is not only a Hausa mindset, but also Islamic,

as reflected in the following

Islamic injunctions respecting the privacy of the individual

(Surat Nur, 24:19):

Those who love (to see) scandal

published broadcast among the Believers, will have a grievous Penalty

in this life and in the Hereafter: Allah knows, and ye know not.

(Surat Nur, 24:27):

O ye who believe! enter not houses other than your own, until ye have asked permission

and saluted those in them: that is best for you, in order that ye may heed (what

is seemly).

(Surat Al-Hujrat, 49:12):

O ye who believe!

Avoid suspicion as much (as possible): for suspicion in some cases is a sin: And spy not on each other behind their

backs. Would any of you like to eat the flesh of his dead brother? Nay, ye would abhor it...But fear Allah. For Allah

is Oft-Returning, Most Merciful.

Hadith (Sayings of the Prophet

Muhammad (SAW)

‘The lowest

of the people to Allah on the Day of Judgment will be the man who consorts with his wife and then publicizes her secret.’

(Muslim)

7 The boka and the Malam are the main spiritual consultants

in Hausa spiritual world, at least for women

who seem to go to either for chants (to a Malam)

or charms (to a boka, as well as Malam) to obtain some powers to control over either a rival co-wife, or a

husband. For detailed analysis of boka Hausa films, as well as Hausa life,

see Mathias Krings (2003) Possession Rituals and Video Dramas: Some Remarks on Stock Characters in Hausa

Performing Arts, in A.U. Adamu et al (eds)(2004), The Hausa Home Video:

Technology, Economy and Society, Kano, Nigeria, Center for Hausa Cultural Studies; Mathias Krings (1997) Embodying

the Other. Reflections on the Bori Pantheon, Borno Museum Society

Newsletter 32&33: 17-29.

8 Incidentally, similar dance routine was popularized in the

1980s by a troupe of shantu (aerophone) music players from Queen Amina College,

Kaduna, and drew similar cultural furor due to the “pump the volume” (“gwatso”, or “gantsare gaye”)

dance routine.

Jurist…

‘One should

not talk about the defects

of others even if one is asked

about them. One must try to

avoid prying and asking personal questions about the private lives of others”

[Al Ghazali, Kitab Adab pp

242-43]

Thus the technique adopted by Hausa

video filmmakers in communicating moral messages

to their audience would seem to clash with these injunctions that respect privacy.

Interestingly, even in India, the focus of the television dramas changed in the 1990s.

According to Mankekar

(2004 pp 418-419),

In

contrast to earlier television shows, the programs of the 1990s displayed an

unprecedented fascination with

intimate relationships—particularly marital, pre-marital, and extramarital relationships—and contained new and varied

representations of erotics (explicit as well as implicit). These programs included soap operas (e.g., Tara [Zee TV], Shanti [Star], and Hasratein [Zee TV]), sitcoms, talk shows

(e.g., Purush Kshetra [Man’s world]

and The Priya Tendulkar Show [both El TV]), made-for-television films and

miniseries, music programs (many of

which were based on songs from Indian films), Indianized versions of MTV, and television advertisements telecast on

transnational networks but produced specifically for audiences in South Asia and its diasporas. The emphasis on the

intimate and the erotic was strongest

in talk shows (which proliferated after the advent of transnational

television), soap operas, MTV-influenced music videos, and television advertisements.

And while the TV in northern Nigeria

reverted to its staid and traditional

self, shedding off its earlier

transnationalism, the changes

in Hindi television heralded the transformation of the Hindi cinema—which

in turn midwifed the new Hausa video film.

As Rachel Dwyer (2000 p. 188) points out, in Hindi films, erotic longing is frequently portrayed in terms of romance

and expressed through the use of song, fetishization,

and metaphor. In most “mainstream” films, she adds, “film songs and their picturization provide greater

opportunities for sexual display than dialogue and narrative sections of the films, with their specific images of

clothes, body and body language,

while the song lyrics are largely to do with sexuality, ranging from romance

to suggestive and overt lyrics.”

Thus despite the sometimes-explicit display

of erotics in song sequences, in terms of narrative

focus, erotics in Hindi films tended to be subordinated to and subsumed

under romance (see Dwyer 2000).

This

is similar to the strategies adopted by Hausa

video film producers who seize the opportunity

to emphasize erotica in their video films, most especially in bedroom scenes. Erotica becomes an essential motif

in Hausa video films because the Hausa society,

like the Hindi popular culture Hausa video filmmakers copy, is a male- dominated society. However, Hindi filmmakers had proven adroit at drawing attention to the

toils, turmoil and tribulations women face in Indian social fabric, and which resulted

in some of the most acclaimed cinema

in entertainment history.

For instance, Mehboob Khan glorified the stoic

strength of a woman in his magnum opus Mother India. Nargis as Radha created an

alluring image of a woman who could be deified. By surviving flood, famine, desertion by her husband, Radha

acquired a Durga-like image. When her

son Birju abducts a girl, she curbs her emotions and shoots him for the greater good of the society. The comparison of Mother India with

Vinay Shukla’s Godmother is

valid because Godmother too

has a woman protagonist and like Mother India depicts how an errant son

proves to be his mother’s undoing. Shabana Azmi in Godmother has

no qualms about

picking up a gun. She refuses to indulge her son and uses her power to get the unwilling target of his interest (Raima Sen) married off to

the man of her own choice. In Asit

Sen’s Khamoshi, Radha (Waheeda

Rehman) epitomized the inner strength

and indomitable resilience of an Indian

woman. A nurse

in a mental asylum, she, too became

a patient of mental illness.

Pre-marital sex in Hindi cinema, at least until recently, generally adhered to two rules:

first was that the encounter

had to be understood by the couple as a genuine and committed “marriage,” suggested by evocations of nuptial ritual (e.g., the prototypical scene in Aradhana, 1979), and two, even a single night’s contact invariably

resulted in pregnancy that,

moreover, produced a male offspring. In Ram

Teri Ganga Maili, the pretext

for Naren and Ganga’s abrupt union is the supposed

“mountain custom” of girls

being allowed to choose their own spouses during an annual full-moon festival (represented by the song Sun Sahiba sun, “Listen, Beloved [I have

chosen you; will you choose me?]”),

as well as the pressure exerted by another local suitor. In a dramatic scene, Ganga leads Naren to a

ruined temple that has been adorned as a nuptial

chamber, while outside her stalwart brother Karan Singh (played by Hindi- speaking Indo-American actor Tom Alter in a rare non-Anglo role) fights off the jilted

fiancé and his minions, ultimately sacrificing his life for his sister’s happiness.

However, with the spate of Westernization and the desire to appeal to wider audiences beyond India’s borders, Hindi filmmakers

had increasingly introduced innovative sexuality in their films

that focus attention

not on the earlier Hindi motif of the heroic

woman, but as a sex object. As noted by a columnist

in India Daily,

“In

recent days Bollywood is tending towards the blue. The core component of the

movies will shift towards the

explicit use of sex, say some experts watching the trends. The reason is simple that is what people want…The

Bollywood bombshells use dummies to perform scenes without clothes. But they cannot perform the lovemaking or

sexy scenes. That is the reason why

directors are looking towards using performers from blue movies in India and

abroad. Trisha Hosania, “Bollywood tends towards blue” India Daily, Sep. 2, 2005.

Indeed, showcasing sex ‘suggestively’

is not novel to the Indian film industry, considering

that there were films like Aradhana (Rajesh

Khanna seducing Sharmila with the

song ‘Roop Tera Mastana’) and Satyam

Shivam Sundaram (Zeenat Aman’s first

film flaunting her body sensuously) which toyed with erotica. Amongst the innumerable that followed, one of the most

talked about erotic film was Dayavan. Vinod Khanna and the much younger Madhuri

Dixit had a passionate scene in the shower.

Even Mughal-e-Azam, a classic of Hindi art film had one of the most

erotic scenes in Hindi cinema, with

a suggested kiss all properly enacted behind a studio prop.

Thus the 1990s saw an increasingly bold

Hindi filmmaking which in actual fact, retrospectively

pay homage to the sensual nature of the Hindi traditionalist icons of Kama

Sutra. This was heralded by the ‘era’ of Hindi filmmakers such as Mallika Sherawat, Neha Dhupia and Isha Koppikar to

name a few. They changed the look of Hindi

cinema and were responsible for a more bold and erotic portrayal of sex in Hindi cinema. Mallika’s seventeen kissing

scenes with co-star Himanshu Mallik in Govind Menon’s

Khwahish took the entire

Bollywood by storm and the industry was shocked at the dare-bare

scenes. Then came Mahesh Bhatt’s

Murder opposite Emraan Hashmi. The film told the story of a

couple that’s lost interest with one another, and the wife ends up finding sexual gratification from her childhood

friend. The film’s success was more

to its heavy reliance on bedroom sequences. Julie, featuring

Neha

Dhupia and Priyanshu Chatterjee was a

breakthrough, both in terms of portrayal of sex and showcasing women.

Jism, starring Bipasha Basu and John Abraham went one step further depicting sexual attraction

between the couple to the extent that the two

decide to get rid of her husband. Karan Razdan’s Hawas, starring Meghna Naidu, Shawar

Ali and Tarun Arora also worked well with the audience because of the generous dose of sex. As observed by

Saibal Chatterjee (2005 p.1) of the new tendencies in Hindi cinema,

Commercial

Hindi cinema has come a long way since the era when directors had to coyly zoom in on a bee hovering over a colourful

flower to suggest the onset of amorous emotions. The revolution has gathered steam especially in the past 12

months with a bevy of former models and beauty queen

daring to drop more than just their

clothes…

Pre-cursors to Censorship

With Hausa video films getting

emboldedned with sexuality, and Malam

Karkata, coming at the doorsteps of Shari’a, it was not surprsing that a censorship mechanism was ignited and provided cassette

marketers with an opportunity to show solidarity with the Shari’a and create the pre-cursor to censorship. This

was because the first organized reaction

against Malam Karkata was

from the powerful

Kano State Cassette Sellers and Recording

Co-operative Society, a loose coalition of cassette marketers.9 In an interview, the Secretary of the

Co-operative explained why the cassette dealers

will not accept

Malam Karkata, even though

it had been certified for public viewing

by the National Film and Censors Board,

Abuja:

“There

are many ways to educate people, if only we can use our brains. What we foresee

in this film is that children will

also watch it, not just adults, and children can pick up bad behaviors from what they see. Since we are

spreading our religion and culture through film, other ethnic groups may despise us. It is for these reasons that

we resolved not to market this film until the producers have cut out the naughty

scenes. We did not say the scenes

depicted in the film do not happen in real life, but

we want control. Even though the producers have been certified by the National Censors Board Abuja for general

viewing, we will not accept it. We are

not in this business for the money, but for the sake of Allah. And we support the government fully

in this”. (Interview with Ahmad Muhammad Amge, Secretary, Kano State Cassette

Sellers and Recording

Co-operative Society on why the Co-operative refuses

to stock and sell Malam Karkata, Tauraruwa, Vol 4 No 6, September 2000, p. 14).

Indeed this prompted the Co-operative

to set up its own censorship mechanisms to filter out films such as Malam Karkata. Since this will obviously affect

producers, the Kano State Filmmakers Association decided to agree to this and became part of the

9 Cassette dealers feature strongly in the marketing of Hausa

video film because most producers do not have the capital to duplicate their videos in large marketable quantities. Thus when a video is completed, the producer gives a master

copy to cassette dealers free, and

then sells the jackets (i.e. covers) of the tape to them at N50 (about

35 cents). The cassette dealer then takes the responsibility of duplicating copies of the master tape,

placing them in the jackets and selling them to individual buyers at N250 ($1.80), or re-sellers at N180

($1.28). The N50 cost of the jackets is all the producer gets out of this deal; even then, the producer is

paid after the dealer has sold the

tapes. The jackets of tapes not sold

are returned to the producer, and the cassette dealer simply erases the tape

and records another video on it! The artistes also do not

receive any subsequent royalties on the sales of the video – having been paid a lump sum by the producer

before shooting begins. However in 2003, a new marketing strategy was adopted

by the dealers – this was the purchase of the CD rights of the films at a N200,000 to N300,000 ($1,428-$2,142) depending on

how flashy the film is (not its storyline is tertiary to first the song and dance in the film, and second

to the stars that appear).

Sometimes a CD right is purchased on the strength of the song and dance

routines, which if the dealer is happy with, he can then advance the producer some cash

for a story to be written!

Joint

Committee on Film Censorship for Kano and Its Environs, set up by the Cassette Sellers

Co-operative in 2000. As announced

to the press by the Chairman of the Kano State Filmmakers Association, Alhaji Isma’il

Marshall:

“A

very important point is that the Kano State Filmmakers Association has set up

an internal committee drawing

its members also from the Cassette Dealers

Association, a sort of Censorship

Board. Every video tape must first be previewed by this censoring

committee, to ensure that it is in consistence with our culture,

before being released

in to the market. We did that to avoid criticism, disrespect to

the Holy Qur’an in some artistes’ dialogs, nudity and other inappropriate behaviors. Once we note these scenes, we

bring them to the attention of the

producers to correct. If he refuses, we will deny him a license to show this

video in any form. These are some of

the efforts we undertake to empower the industry.” (Alhaji Auwalu Isma’il

Marshall, as the then Chairman

of the Kano State Filmmakers’ Association, Interview, Fim, August 2000 p. 14).

This

committee on censorship, became the effective

watchdog of the film industry

in Kano. In a public

announcement the committee issued out a circular on Sunday 18th July 2000 warning

film makers to avoid the following in their films:

1. Sexuality – in language

or action

2. Blasphemy

3. Nudity

4. Imitable criminal

behaviors

5. Violence and cruelty

6.

Other video nasties

that can come up from time to time (my translations from an advertorial in Tauraruwa, Vol 4 No 6, September 2000, p. 27).

However, no sooner had the co-operative

started working than complaints started trailing

it. Quite simply, many producers refused to allow their films to be censored by the marketers—something they can do since the censoring was voluntary and had no legal backing. A specific case in

point was a then newly released film, Tazarce (Kano, 2000) which the producer

released in the market without waiting for the

certificate from the marketers’ censoring committee. In an interview, he

stated his reasons for breaking the censor’s rules:

“What

they have done to us is not fair, unless they have a hidden agenda in

preventing our progress. We have been

to Abuja (NFVCB) and they have cleared us. We came to Kano and they (marketers’ censoring committee) also

cleared us and suggested corrections which we

did; yet they refused to issue us with a certificate. So we decided to

ignore them and sell our film

directly to the market”. (Sani Luti, Producer, Tazarce, defending breaking the censorship rule in Kano, in an interview with Mumtaz,

September 2000 p. 13).10

Further, older producers accused

the marketers of divide-and-rule strategies by breaking ranks

and sneaking to individual producers to get their films released without

certification. Younger producers claimed that the major producers

always get away without their films being

censored, and that the arrangement was done to favor the older and more established producers. Yet others alleged

corruption and bribery

to circumvent the censoring

mechanism.

It is significant that the major

complaints were not against creative

observations of the censorship

committee, but against the logistics of censoring. In order to create a more acceptable formula

for censoring, the marketers invited the Kano State

10 The full details

of the meeting are given in Mumtaz, September

2000 pp 13-14).

Filmmakers Association to a meeting held on 21st August 2000 to discuss

the issues. Some of the problems of censoring were

highlighted by one of the members of the committee, Dan Azumi Baba,

a veteran producer:

“We

called this meeting to discuss the issues (of censorship). You set up our

committee, and unless we do something

about the current situation, then some of us would have no option than to resign from the committee. Many

things bother us about what we doing. For instance, a producer would come and insist that he is in a hurry and

demands we should issue a certificate

to him, despite the fact that there are other producers waiting for their turn.

Other producers sabotage our efforts;

yet others accuse us of stifling them”. (Speech of Dan Azumi Baba at

the joint meeting of Cassette Seller’s and Filmmakers, Kano, 21 August, 2000,

in Mumtaz, September, 2000 p. 13).

The Chairman of the meeting, Musa Mai

Kaset, defended the committee against any accusations:

“Since

we started, no one has come to complain about batsa (obscenities) in any tape we sell. We also receive tapes from other States in the north for censoring, and the producers are always happy with out suggestions. Yet

shamefully, it is only in Kano that we face problems with producers. There ought to be a law that should apply to the

process of making films, not just

selling them”. Speech of Musa Mai

Kaset at the joint meeting of Cassette Seller’s and Filmmakers, Kano, 21 August, 2000, in Mumtaz, September, 2000 p. 13).

It is interesting therefore that it is

the industry that has started demanding for a “law that should apply to the process of making films”. At the end

the meeting agreed to continue with the censorship process instituted, and fine any producer who refuses to co-operate

with the censorship committee the sum of N10,000 (about US$76). This fine also applied to any marketer who

stocks and sells an un-censored film. The producers of Tazarce which heighten

the problem, were fined N3,000

(about US$23). It was clear therefore that censorship, even if self-imposed by the practitioners, would have problems.

Bush War: International Politics and Hausa Video Censorship

On Tuesday September 11, 2001 two

hijacked airlines smashed into the twin towers

of the World Trade Centre in New York. A third hijacked plane slammed

into the Pentagon in Washington and a

fourth one crashed in Pennsylvania, apparently out of control. The United States blamed Osama bin Laden and his

al-Qaeda Muslim network, suspected to

be hiding in Afghanistan. This

prompted a US military action against

Afghanistan. In Kano thousands of youth participated in marches of support and jubilation for Osama bin Laden as a

result of this attack. Osama bin Laden was instantly

seen as a folk hero, and a boom in naming newly born male babies Osama ensured. Hundreds of Osama bin Laden

T-shirts and posters became available in Kano.

On 7th October 2001, a rally was held

in Kano to support Osama bin Laden and protest

American raids on Afghanistan. The issue of Osama bin Laden in Kano was therefore taken extremely seriously by

government officials and security agencies. Thus

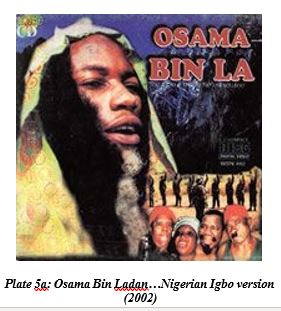

there was a great unease when in 2002 a “Nigerian film”, Osama bin La (dir. Mac-Collins

Chidebe) was released and sold in Kano. It was in Igbo language and created

furor in Kano over its portrayal of Osama bin Ladan as a crook and fraudster. Plate 5a shows the video’s

poster.

Government security agencies were

horrified that the video found itself into Kano markets. The “Nigerian” film market, controlled principally by

Igbo merchants in Kano exists

virtually independent of the Hausa home videos in Kano, and follow a different marketing and distributing

network. The concern in Kano over Osama

bin La was that it could generate

riots – in a polity where Osama bin Ladan was seen as an Islamic jihadist. The video was quickly banned by the

government (not even the Censorship

Board, which was not aware of the film in the first place), and Hausa cassette

dealers throughout northern

Nigeria refused to stock it.11

Right

in the middle of this, a

the trailer and poster for a new Hausa home video, Ibro Usama was released. When Igbo film makers released

Osama bin La only

the security agencies

were aware of it. However,

when Ibro Usama was

announced, the religious

establishment took immediate notice. Since the Ibro series of Hausa video were essentially

slapstick comedies (with lots of facial pulling), and still fresh from the devastating attack on the Muslim scholar

class in Ibro’s Jahilci Ya Fi Hauka,

there were fears of repeat

performance; this time, the short end of the stick would be an international jihadist hero. There was an immediate outcry against the film even before it was released. Plate 5b shows the poster

and stills from the film.

11 Interview with Mohammed Dan Sakkwato, major

cassette dealer, Kano, October 2004.

Plate 5b: Bush War: Osama bin Laden vs. George Bush – Hausa Home video versions

The film actually details the American

war against Afghanistan and the comedic antics

both sides went through to execute the war. The script was poorly written and shows a significant lapse in the film producers’ understanding of the war.

For instance, the “Taliban ambassador to Pakistan” seems to prefer to make announcements

on the Lebanese satellite station LBC, rather than Al-Jazzera. But then the film was not meant

to intellectually challenge; but to provide,

literally, comic relief to a serious subject matter. This

point was lost on northern Nigerian Muslim scholar

establishment who seized every opportunity to condemn the film and its makers.

For instance, the Hisbah— an Islamic

vigilante group—under the then leadership of

Sheikh Aminuddeen Abubakar went to the length of writing a protest

letter to the Kano State Censorship

Board, urging for a ban on Ibro Usama.

However the Board insisted that they

had seen the film, and saw nothing wrong it with it from Islamic point of view. Indeed the Board even

invited the Hisbah to come and watch the film

in the Board’s viewing room.

The Hisbah did not accept

the offer.

Due to the significance of the reason

for Ibro Usama within the context of

the interface between international politics

of the military industrial complex

and Islam, I am

including the original Hausa language rationale for the film given by

producers, and an English translation:

(“Dalilin

da ya sa na yi tunanin k’irk’iro Ibro

Usama (shi ne) saboda shi dai Usama (bin

Laden) mutum ne wanda ke son addinin Islama. Kuma mutum ne wanda yake

nunawa sauran k’asashen duniya abin

da ya kamata. Shi ne na ga ya kamata mu yi fim da sunansa domin mu nuna wa duniya duk wani Musulmi ya koyi irin abin da Usama yake yi domin samun ci gaban Musulunci baki daya”).

“The reason

for Ibro Usama is

that Usama bin Laden is a true patriotic Muslim.

He also shows other nations

what is proper. These reasons prompted me to make a film about him so we can show me to the world as a model for

every Muslim to copy his actions in order to further the cause of Islam”. Malam Mato na Mato, Potiskum, Yobe State,

Nigeria, Production Manager, Ibro Usama, interview with Fim magazine, August 2002, p. 22).

While

this statement is apparently made in the spirit of Islamic patriotism, nevertheless it could also be interpreted as a loaded messaging

encouraging the actions of the real Usama

bin Laden, whatever those actions and their consequences are. It was surprising that this particular point was not a focus

of concern either

by the religious establishment, or by the Government. This further emphasized the

indifference with which the mainstream

religious establishment and government agencies

treat the entire the Hausa home video industry—unless it either touches, or sparks

off “security” issues.

The film and its producers attracted a

softer form of fatawa in the form of

“tsinuwa” (curse) at mosques during Friday prayers at Bayero University

Kano, Wudil (where the cast and crew of Ibro Usama were based)

and Kaduna. The principal character

in the film, Rabilu Musa

Danlasan, who played the role of Osama bin Ladan, was defiant in an interview, about his role in the film.

“We

as Muslims will never do anything injurious to Islam, but we will draw

attention to how to strengthen Muslim

practices in our communities. I am also very happy with the furor Ibro Usama generated, people abused and cursed us in mosques

all over. Yet surprisingly when the film Ibro Usama came

out, they saw it was not as they expected

it. Ibro is not a Christian, or a pagan.

Ibro is a Muslim, thus he will never do anything to damage Islam.

But due to ignorance of wandering Malams (malaman haure – insultive, “not son of

the soil”, wanderer) they attacked my

role in the film.” Rabilu Danlasan, “Ibro Usama”, interview, Fim, August 2002, p. 15).

Eventually the furor died down and the

film enjoyed moderate sales due to the curiosity

factor it generated in many people who wanted to see what the fuss was all about.

Islam and the Video Star

The Islamicate establishment had,

hitherto, developed an uncertain stand towards

Hausa video films.

Most were convinced

by the arguments provided by the producers

that the Hausa video film has weaned off Hausa youth from watching Hindi

films. Also at every opportunity, the video film artistes and producers explain

their vocation as educational (ilmintarwa), religious (wa’azantarwa),

and more or less harmless entertainment (nishadantarwa). In Kano and other parts of Muslim northern Nigeria,

in the light of impending

Shari’a launch, Islamic

scholars who had remained indifferent to the industry, suddenly

started bickering amongst themselves about the

merits or demerits

of the new entertainment medium,

and camps rapidly

developed.

The first cluster maintains a neutral

stand, giving the usual stock answers about the legality of the subject matter of the film storyline, rather

than the practice of the filming

itself. In particular, the Izala12 leaders were cautious about the

role of film in a Muslim polity.

For instance, Sheikh Umar Hassan, an Izala leader in an interview with Fim (September 2002, p.34) urged Muslim organizations, especially the Jama’atul Nasril Islam (JNI), an umbrella

organization of Muslims in Nigeria, to embrace

the film industry and shoot their own films which should preach unity among the Muslim polity. Interestingly enough,

the former Secretary General of JNI had something to say on the issue, when approached by journalists. As he stated,

“A

young man, full of braggadocio, but ignorant of Islam or professional knowledge

of the film industry will just enter

into the profession. And yet the authorities are doing nothing about it, because to them it is just

entertainment. Yet they don’t know where these films can end up. That is why we feel time has come for a system that will

protect Islam. There should be a

Censorship Board that will provide rules and regulations to bind every film

producer, whether young or adult. This Board should censor

films by watching them to ensure they will

12 Jama’at Izalat al-Bi’a wa Iqamat al-Sunna, a modernist Islamic movement established in 1978. For details of the Izala movement in Nigeria, see Kane (2003).

not

harm the public, before being allowed to be sold.” (“Jama’at Nasirl Islam ready

to contribute to improvement of Hausa

films”, translated interview with Alhaji Jafaru Makarfi, former General

Secretary of JNI, Fim,

December 2002, p. 33).

A second cluster

of Islamic scholars

cluster condemns, in totality, the entire phenomena

of entertainment. This was revealed

during a meeting

held on 9th August 2002, when the Muslim Sisters

Organization (MSO) an NGO of Muslim women in

Kano, convened a meeting between various Islamic scholars in the State

and some video film producers, to

understand each other. The meeting was held at the Sani Abacha Youth Center,

and was interestingly enough, poorly

attended by the members of the video film industry themselves.

Consequently the dialog was more or less one

way, and the Muslim scholars

used the opportunity to color their views with the Saudi

Arabian version of moral policing

in a contemporary society.

Ustaz Bin Usman, for instance, in his

presentation categorically stated that Hausa

video film production should be stopped immediately, since “Allah did

not create us for (our) amusement,

but to worship Him”. He urged the video producers to choose another

vocation. Malama Aishatu

Munir Matawalle suggested that the film industry was introduced into the Muslim northern

Nigeria by the Europeans to destroy Islam,

“since some of the scenes were described in the Prophet traditions as

reflecting the behaviors of the

denizens of hell-fire”. She urged Hausa video film producers to produce videos in accordance with Islam.

Malam Farouk Yahaya Chedi an Islamic scholar and

lecturer in Islamic Studies at Bayero University, Kano, also condemned both Hausa videos and contemporary Hausa novels since they “promote

alien cultural values,

such as those of India, nudity and chasing women…”13 Only Alhaji AbdulKareem Mohammed, the Chairman

of MOPPAN representing the Hausa video film

industry presented a paper in which he defended their craft, and also

challenged the Islamic scholars to

become producers and produce the sort of videos they feel should be done. This challenge was

actually taken up by one religious group, the

Shiites.

Thus a third cluster of Muslim scholars

saw nothing wrong with the video films, so long

as they were produced according to Islamic tenets and the culture of the Hausa people; and almost without any exception,

they decried the Hindi cinema-style singing and dancing in the videos.

Those in this category included

individual Muslim scholars such as Ustaz Yusuf Ali, as

well as organized religious groups like the Shiites,

or as they refer to themselves, Muslim Brothers, who embraced the new medium precisely because they noticed its

potential in reaching out to a large, young urban audience, and could therefore be used as a recruiting and indoctrinaire mechanism. This is revealed

in an interview with Malam Ibrahim Yakub El-Zakzaky, the Shiite leader

in Nigeria in which he stated his organization’s stand

on films:

“I

urge Hausa film producers to protect our culture and Shari’a. Whatever they

should do in the name of

entertainment should not be against Shari’a. We thank Allah that from within

our organization some of us have

started thinking of producing our own films (“The position of Films in Islam”, Interview with Malam

Ibrahim Yakub El-Zakzaky, the leader of “Muslim Brothers” (Shiites) in Nigeria, Fim September 2001, p. 52).

13 Conference report,

Wakiliya, No 2, December,

2002, p. 17. Kano.

The caution which with the Shiite

treated the Hausa video film industry was later revealed to be calculated, because of their

intention to engage

in the industry; it would look

contradictory to condemn the medium on religious basis. Thus the Shiite in northern Nigeria, instead of breathing

fire and brimstone over the salacity and de-

acculturation of Hausa video films, took to making their own,

preaching their messages in the way they felt their

followers would most easily absorb — in effect

using the same communication channels to reach to a wider audience; the

video medium therefore became a powerful ideological tool for reaching

un-tapped territories. To this

end, about eight Shiite-flavored Hausa video films were made at the forefront of the re-introduction o the

Shari’a penal code. These included Mace Saliha: Tsiran Al’umma, Shaheed, Karbala, Sanin Gaibu, Mujarrabi, Taubatan Nasura and Arba. Similarly, Al-Tajdid, a splinter

Shiite group in northern Nigeria also

produced Tafarki (2002) which focuses

on the consequences of Shari’a law implementation on non-Muslim communities.

Enter the Dragon — Censorship Arriveth!

These controversies and cultural

criticisms merely added the fuel to the fire that was raging. The Shari’a, first announced in Zamfara State served

as the trigger.14 On 27 January

2000 Zamfara State re-enacted the first Shari’a Penal Code in Northern Nigeria.

Shari’a courts had already been established earlier.

The example of Zamfara was followed by Niger (May 2000), Sokoto

(May 2000), Katsina (August 2000) Jigawa (August

2000), Yobe (October

2000), Kebbi (December

2000), Bauchi (March 2001), Borno (June 2001), Kaduna

(November 2001). In December 2001 Gombe announced its intention to launch the Shari’a, but civil protests

from Chrstian groups made it impossible. Similarly,

Kwara State made the attempt to introduce Shari’a

in November 2001 when some Muslims in the State forwarded a bill to the State House of Assembly, calling

for the introduction of Shari’a.

The Kano State Government re-established the Shari’a penal code in June 2000, but it was made effective from November of the same year to coincide with the holy month of Ramadan. The announcement of the new penal code was received

with trepidation by filmmakers, since it was clear that

with a new law in force, filmmaking was to be

affected. In particular, how the films portray Islam and Muslim peoples

in a deeply conservative society.

Government officials in Kano—just as had happened with Hausa novelists in 1990s—had by 2000 started getting worried

about the spate of complaints about the cultural

consequences of the new media. For instance,

in a letter to the History and Culture Bureau,

the Office of the Special

Adviser to the Chieftaincy Affairs

in Kano noted:

We have noted with concern the proliferation of the production of local Hausa films. This may be a welcome development, as it will

help in the general development of indigenous film industry. However, we have received many complaints regarding

some of this films (sic) and the way

they are corrupting our religion, culture and good traditions and eating deep

into our social fabric. The impact of

these films unfortunately are more devastating on the vulnerable members

of our society, children, youth

and women.

14 Some form of Shari’a has

long been part of Nigeria’s legal code in the civil law governing marriage and inheritance. Its re-launching in

1999 in Zamfara State (and soon followed by about 12 other states in northern Nigeria) was part of Islamic

re-awakening in Nigeria occasioned by a new democracy in 1999 that provided

for greater freedom

of religion than in the previous military

regimes.

The HCB was consequently requested

to provide a report

“regarding this new phenomenon” that should focus on:

1. Statistics on the number

of these film producers, distribution outlets, number of films produced, cinema houses (official

and unofficial) these films are shown for a fee.

2. The nature of the regulatory environment and its effectiveness

3. Assessment of the social

impact and behaviour change among the vulnerable groups.15

It is instructive that although the

Hausa video film industry was born in 1990, yet 10 years later in 2000 government officials do not seem to have

any specific records of its growth

and development. This would seem to reflect

government’s indifference to the

industry, and the focus on regulation was a beginning of a process of

controlling it.

Soon

after the Shari’a

announcement in June 2000, the Kano State

Government set up a

publicity committee to hold dialogues with producers of Hausa video films to discuss the modalities for regulating the

contents of Hausa video films produced and

distributed in Kano.16 On 29 June 2000 the committee held a roundtable meeting with filmmakers in Kano to discuss the

issues. It was a heated meeting, with government team insisting on regulating the industry according

to Islamic rules,

and based on the constant complaints of parents

and other community leaders about the contents of the storylines in the videos.

Significantly, the government team also informed

the gathering that they have heard that a hardcore

pornographic video is being planned

in Kano. This was actually

based on an interview in a magazine that has just been published. The interview was with a noted Hausa TV drama and

stage actor, Shehu Jibril, aka “Golobo”, who stated that:

“…I could foresee that Kano producers may even produce

a hardcore pornographic film (bulu fim),

since the trend started from where they are heading. In the fast, Indian films

don’t have even kissing scenes, but now Indian films include that scenes are

amorous and are radically different

from how they started in the film industry. Also the creativity of Indian film

makers has finished…Thus the trend of

Indian films now is likely to lead to a hardcore pornographic Indian film, and it won’t take long for

Kano video film producers to do the same because they faithfully copy whatever

Indians do in their films…”(Interview with Shehu Jibril,

aka “Golobo”, “Kanawa

Za Su Yi Bulu Fim” (Kano producers

will soon film hard core pornographic movie”)

in Garkuwa, April 2000,

p. 10).

The views that Hindi films were getting

steamier, and since Hausa video film producers copy almost anything Indians do

in their films, subsequently Hausa video films would soon start more erotic

scenes are echoed

in a similar observation of Hindi cinema

by Jonathan Groubert

of Radio Netherlands who noted that

Anyone

who has watched any Hindi Cinema knows that sex is something implied rather

than done. Dances are sensual

and erotic, faces are brought

close together in a breathy

embrace and yet…the lips never quite meet. The 21st century has seen a few screen kisses. The

recent blockbuster Mohabbatein featured a particularly

steamy one and, so far, it seems few feathers

were ruffled. Nudity,

however, is still far away.

But costumes over the last decade have gotten

15 Special memo from the Office of Special Adviser on

Chieftaincy Affairs, Office of the Executive

Governor, Kano State,

to Executive Director,

History and Culture

Bureau, Kano, Ref SAC/ADM/4/1 of 19th January,

2000.

16 Government had no regulatory mechanism for southern

Nigerian and films imported from overseas – the

precise arguments Hausa film makers had against censorship, since they feel it

was unfair for only their works

to be subjected to regulation while imports are not affected.

skimpier,

and the bodies of both actors and actresses have become more taught. Gone are

the days of cheery double chins and

predictable paunches. Nowadays muscles ripple and breasts heave.17

During the Kano meeting, it was pointed

out to the government team that foreign films,

freely imported into the country, and obtainable through subscription satellite channels show worse content than any Hausa

video. Further, films from southern Nigeria, freely available in Kano markets,

also often contain